Focus

On Fuel Failures

In

the 16 months since fuel related incidents were last discussed

in Callback (#283 April, 2003), 47 reports

have been submitted to ASRS regarding preventable, fuel related,

forced landings. The NTSB database contains a similar number of

forced landings caused by fuel problems for the same period. The

NTSB events were classified as accidents due to significant damage

and/or injury and therefore were separate from the ones reported

to ASRS.

Failure

to monitor actual fuel usage, a factor cited in many fuel starvation

incidents, was covered in Callback #283. Two additional factors

that recur in both the ASRS and the NTSB reports are:

1.

Failure to select the appropriate fuel tank

2.

Failure to visually confirm the fuel on board during preflight

The

following ASRS reports present some lessons learned regarding

these two additional "fuel failures."

Tip

Tank Tip: Select the Full One

After

selecting the wrong tank, this PA32 pilot found himself in a field

with fuel to spare.

My

airplane has four fuel tanks. Three tanks were full and one

was empty. I did not fill the right tip tank because of [a fuel

transfer problem]. After takeoff, the airplane was heavy on

the left side and required a lot of right aileron. I decided

to burn some fuel from the left tip tank to balance the airplane.

I moved the fuel selector valve to the empty tank instead of

the full tank. The engine stopped and I started the emergency

procedures. I checked the fuel pump and magnetos, called ATC,

and looked for a place to land. We made a successful landing

in a field. I made a pilot error by not checking the fuel selector

valve and also by flying the aircraft with a known fuel problem

in the right tip tank....

Another

Selection Suggestion: Avoid the Empty Tank

This

BE35 pilot also inadvertently made a wrong selection and then

failed to check the fuel selector position. Luckily, a second

pilot was available to land the aircraft while an attempt was

being made to pump some life back into the engine.

Prior to entering the traffic pattern

for landing on Runway 17, I thought I had selected the fullest

fuel tank. On the turn from base to final the engine lost power.

I thought I selected the correct tank, but I was wrong. I continued

to pump the wobble pump trying to get fuel to the engine to

no avail. While I was pumping, the other aircraft occupant was

flying the airplane and was able to land the aircraft safely

in a field with the gear up. No major damage or injuries occurred.

Visual

Verification

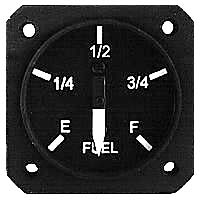

As

this C150 pilot learned, relying on fuel gauge indications alone

can lead to an unexpected arrival... down on the farm.

...The

plane had been flown previous to our flight, but the fuel gauges

showed over 3/8 of a tank in the left tank and 1/2 tank on the

right gauge. I flew to a couple of neighboring airports for

touch and goes.... After maneuvering in the area of the second

airport, I headed for home. At each airport, I noted the fuel

level. I could have stopped at an airport that I flew right

over, but the right gauge showed 3/8 of a tank and the left

indicated slightly less than 1/8 of a tank. I was 30 minutes

from home...and could see no problem, based on the gauges. 15

minutes later, at 2,500 feet AGL, the engine quit. I attempted

a restart with no success.... I landed in a large farm field

with no damage to the plane. Both tanks were found to be empty.

The incident was caused by relying on the fuel gauges instead

of checking fuel levels visually and not confirming the amount

of flying done previous to my flight.

Although

the PA28 pilot who submitted the next report did check the time

logged on the previous flight, the aircraft fuel log was not checked.

The gauges and a visual estimate of fuel remaining proved inaccurate.

If the tanks are not full, a visual estimate of the fuel remaining

is just that, an estimate.

...After

visual inspection of the tanks, I estimated that there was more

than three hours of fuel remaining. The logbook showed that

the previous flight was 2.2 hours. With this in mind and useful

fuel available of 5.5 hours for full tanks, I assumed that 3.3

hours of fuel remained. After start-up, the fuel gauges showed

1/2 full in both tanks. I was still thinking there was at least

three hours of fuel available. Maximum time of the flight was

figured at two hours. After 1.4 hours of flying, the engine

quit and a successful landing was made in a farmer's field with

no injuries or damage to the plane.... After reviewing the logbook

on the fueling of the airplane, it showed that the plane had

not been fueled the morning of the incident. Checking the fuel

logbook with the plane's logbook, it was determined that the

useful fuel on board the plane was only one hour....

A

C182 pilot filled the tanks himself and, therefore, did not see

any need to bother with a visual check. This report to ASRS points

out why a pilot should always confirm the fuel on board.

A

landing was made in a field due to engine failure. The day before

this flight, I had filled the aircraft fuel tanks. When I arrived

at the airport I did not visually check the tanks. I later learned

that a local mechanic had done a weight and balance on the aircraft

the previous evening. In doing so, he drained all fuel from

the aircraft. He did not put the fuel back in the tanks when

he was done. The aircraft fuel gauges were so far past empty

that they appeared to show full.

Preflight

Hindsight

The

better prepared a pilot and his or her aircraft are before flight,

the safer that flight will be. Since a thorough preflight is a

vital step in that preparation, these recent ASRS reports are

offered as valuable lessons on avoiding preflight pitfalls.

A

Casual Cap Check

Loose

fuel cap incidents are reported to ASRS on a fairly regular basis.

Some aircraft, such as the C182 in this report, may require a

ladder to enable a hands-on preflight of the fuel cap security.

After

reaching 1,300 feet, I noticed fuel leaking out of my left wing.

I then glanced at the fuel gauge and saw that my fuel level

was dropping rapidly. I notified Departure [Control] and they

gave me priority back to [departure airport]. I landed without

incident. When I checked to find what the problem was, I found

that a fuel cap had come undone. I had failed to check the tightness

of the fuel caps prior to departure. During preflight, I checked

to see if the caps were on, but I didn't get on a ladder to

check the tightness. This incident could have been prevented

if I had done a complete preflight and checked the fuel caps.

Latest

Flying Fashion: Accessoires pour l'empennage

With

his wife's help, this pilot gave new meaning to the term "flight

jacket."

I

preflighted the aircraft and all was well. Fuel and oil were

full, chocks out, tie downs removed, and everything seemed ready.

My wife and I then loaded several bags and other items and I

seated myself in the cockpit while she departed for home. The

taxi out and run-up were normal.... The takeoff roll seemed

OK, but upon rotation, there seemed to be a slight vibration

in the controls. Then as I was climbing through 1,100 feet,

the vibration got slightly worse, which didn't seem normal to

me, and I elected to return to [departure airport]. I informed

Tower that I had some sort of control problem and needed to

return. Landing clearance was granted at once. The landing was

uneventful, but as I was taxiing in Tower informed me that there

seemed to be something on my right horizontal stabilizer (not

visible to the tower on taxi out and takeoff because it was

on the opposite side). I taxied to the run-up area and someone

from the airport staff removed my jacket from the stabilizer

and handed it to me.

The

jacket had been set down on the stabilizer by my wife and, in

the loading process, simply forgotten. I boarded the aircraft

from the side opposite the jacket, so I didn't see it either.

The vibration in the controls was the jacket flapping in the

wind, but I had no way of knowing that and assumed the worst.

Had I elected to continue the flight, the jacket would most

likely have blown off, but the possibility exists that something

worse could have happened and I could have had a severe control

problem. The decision to return upon sensing that something

was not normal was probably a good one....

In

the future I will load first and then perform the preflight.

From

Bad to Worse

Haste

is often cited as a factor when safety is compromised. In the

following report, the result of a C172 pilot's hasty preflight

was bad, but his solution was worse.

An

airshow was scheduled to begin in about a half-hour. I was told

by Ground Control that I had two minutes to get into position

and take off. In my hurry to comply with Ground Control I forgot

to remove the tow bar from the front of the plane and began

to taxi. The problem was pointed out to me by people [along

the taxi route]. I compounded the problem by removing the tow

bar without stopping the engine. I was lucky not to be injured!

Lesson

learned: Do not let anyone or anything cause you to hurry. That

is when mistakes happen that can lead to accidents.

Shed

a Little Light and Avoid the Runaround

A

B737 Captain submitted these observations on the proper equipment

required for a proper preflight.

The

flight was running extremely late when my reserve First Officer

arrived at the aircraft. I decided to do the walk-around so

that he could get settled in the cockpit. I asked to borrow

his flashlight and he handed me a penlight. He told me that

it was the only flashlight he carried.... As a Captain I am

very uncomfortable with the thought of a preflight or postflight

check being accomplished in the dark with a penlight.... We

are responsible for ensuring the airworthiness of the aircraft...and

this responsibility requires that a proper preflight be accomplished....

On

the subject of preflight and postflight [inspections], the weather

is turning colder back east, but is still warm in the west.

Pilots need to remember to bring appropriate clothing (i.e.

a warm jacket) to ensure that a cold weather walk-around does

not become a run-around.